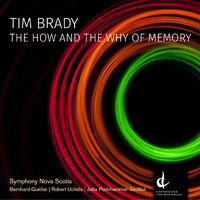

by Tim Brady ¦ September 20 2017

“Hello, my name is Tim I’ve been an Omnivorous Listener since I was 18 years old.”

There, I’ve said it.

Drawn to music by The Beatles and the 60s musical and social revolutions, I moved on to jam-rock, fusion, jazz, orchestral, chamber, experimental, you name it. By the time I was 21 years old I was just as likely to be caught listening to The Allman Brother Band as to Stockhausen or Charles Mingus.

The crazy digital explosion of the past 15 years has really only made my already omnivorous listening habits easier to manage. I no longer need to haunt used record/CD shops, looking for some amazing, unheard of discovery at a bargain price. I don’t need to check out every issue of The Wire or Downbeat (substitute magazine of choice) to see what is going on. The Internet has made things simpler, but it has not really changed how I listen, or what I listen to.

But what I listen to and how I listen has changed over the years, for several reasons. This article, I suspect, will end up being about how and why I listen to music now, as much as it will be a discussion of what music I listen to.

The most obvious reason I listen to music differently now is that I’ve been doing it consciously (choosing what listen to) for over 55 years. That’s a lot of notes, my friends! Of those 55 years of listening, 40 of them have been as a serious student of music (and, as a professional musician and composer, I am a perpetual student of music). I imagine many of you are in a similar position, though perhaps with a bit less mileage on the odometer.

Initially we are all overwhelmed by the power and beauty of music – it seems inexplicable, that is what draws us to it. Why do I care so much about sounds floating in the air? About people practicing thousands of hours to control some bit of acoustic-mechanical machinery that transforms our human thoughts, combined with finely wrought muscle control, into a form of collective auditory hallucinations? I’m still really not sure why, but it is clear – we really do care.

So for many years I listened because I wanted to understand how it was done.

How does Debussy seem to stop time? How does Miles Davis control that seemingly ephemeral yet perfectly structured flow of those late 60s and early 70s ensembles?

How does Arvo Pärt make A minor seem new? W hy can I listen to yet another guitar solo by a jazz master like Pat Martino and still be amazed?

hy can I listen to yet another guitar solo by a jazz master like Pat Martino and still be amazed?

I don’t have all the answers, but I now have a sense of how the mechanics work. As a composer, this is a start. So when I hear something, I can now parse out the components – harmony, texture, form – so that I am always aware of what is happening, even if we can never truly know the “why.” This professional ability to pull music apart is essential – it is how you become a decent composer. It also fundamentally changes how you listen. At least, it has for me.

Increasingly, I truly appreciate music as a LIVE performance (an odd statement for a man releasing his 23 and 24th CDs this year, admittedly). Increasingly, music is becoming  more about the act of music making. The sounds are, of course, important. But they are not the longer term goal – it is the very act of struggling with the instrument, of working with other musicians, of reacting to the audience, that makes music making have its profound impact on us. In effect, I am now more interested in listening to music making, not just “music.” This is a subtle but real shift in focus.

more about the act of music making. The sounds are, of course, important. But they are not the longer term goal – it is the very act of struggling with the instrument, of working with other musicians, of reacting to the audience, that makes music making have its profound impact on us. In effect, I am now more interested in listening to music making, not just “music.” This is a subtle but real shift in focus.

So I have two modes of listening. Real listening pleasure is mostly in concert. Not that I don’t enjoy a good recording, but the emotional pleasure, and the sense of “losing one’s self in the music” is greatly amplified in concert. For me.

Listening to recorded music is more about discovery and learning. Or, sometimes, it’s about simple emotional nostalgia (listening to old Beatles’ tunes is a powerful drug to baby boomers). When listening for discovery and knowledge, I am still that perpetual music student.

The other two reasons I listen to music differently now are also age related, but quite different.

Having recorded and produced 24 CDs, you end up hearing music in such micro detail that it becomes, at times, almost a handicap to listening. I have just finished 12 weeks of mixing and editing (2 big new CDs) and, during that period, I could not really listen to any other music. My listening had become so analytical (essential for this part of the CD process) that other music was just a jumble of auditory details to be managed, not a unified whole. So I have to be careful about balancing this “producer/listener” with the “music/listener.” They are two different hats.

The other issue is tinnitus. Since May 13, 2007 I have had minor tinnitus in my left year – a very high hiss that is constant, though it does not impeded listening at all. I’m used to it, no problem. But it has had a few effects. I carry earplugs with me now – really loud sounds clash with the tinnitus in a somewhat unpleasant way, so I try to avoid them. I wear a discrete earplug in my left ear on stage, just to not have to worry about that issue.

It has also made me aware of the very peculiar nature of “hearing.” Earlier, I spoke of “auditory hallucination” – that is, in fact, what tinnitus is. There is no sound, but you hear one. So I now wonder about how our brain processes real sounds. What are “real” sounds? What is the link between the sounds that we hear, the sounds our brain process, and our reaction to them? Is this real or is it some form of “magic”? The oft-used term “emergent property” comes to mind – an experience that is greater than the sum of its parts. But that only gets us 90% there. How, where and why does that final 10% come about – why does music provoke such passionate reactions: it’s just a bunch of frequencies that our brain somehow believes have form and coherence.

One of the tricks I learned to deal with tinnitus is to make a clear distinction between what your brain is doing, versus what is “real” (external – if we define that as more “real’). To not believe or take into account everything that our brain pushes forward as “real.” Anyone familiar with Cognitive Behaviour Therapy will recognize this approach, and it was very useful for dealing with tinnitus. But it did change how I listen to sound and music, without a doubt.

So – what the hell am I listening to???? With or without earplugs, tinnitus, or OCD-level technical analysis?

My main source for recorded music these days is Youtube. And random suggestions from my Facebook feed. This stream of interesting and often exotic music is really the only thing that keeps me on FB (aside from being an excellent place to come across a good joke!).

From a Facebook feed to Youtube sites, I recently listened to classical guitarist Julian Breem improvising (quite well, I will add) with Indian classical sarod virtuoso Ali Akbar Kahn. From the late 1960s.

This lead me to an early 60’s film of Ali Akbar Kahn playing with a very young Ravi Shankar.

Man, those folks can really, really play. The sense of timing is truly breathtaking – they serious traffic in “magic.”

There is a great clip I’ve seen a few times of Paul McCartney doing an alternate take to “Hey Jude.” Same arrangement, same melody, same band, same session. But it just does not have the magic of “the” take. After this competent but unremarkable take, producer George Martin leans over into the talk-back mic and simply says something like: “That’s not the one, Paul”. Needless to say, they did finally get “the” take. But it is a really interesting window into that o-so-famous creative time and place.

In a totally different direction, there was Schoenberg’s String Trio. A fairly late work (1946), it is not as methodically and purposefully atonal as the middle period (at least, from a casual listening). Aside from the 12-tone harmonies, which vary from quite consonant to somewhat dissonant (though never approaching the more contemporary clusters or noise) – I was struck by how the phrasing, rhythmic articulation, gestural vocabulary and formal development really are quintessentially late 19th century Viennese – nothing revolutionary on that level. You can take the boy out of Vienna, but you can’t take the Vienna out of the boy.

Then there are guitar players. I am one of them.

It seems the Internet has unearthed every film and video of every guitarist ever known to have graced the stage with a Stratocaster and a Marshall amp. Some are pretty good.

Fusion guitar player John McLaughlin has been a long-time influence, and some of the performances from the 70s (with his Mahavishnu Orchestra) have surfaced from European festivals. McLaughlin and the band are pretty serious, but the most amazing virtuosity at times comes from the often-overlooked violin player Jerry Goodman.

And for sheer technical hijinks, country players like the late Danny Gatton, or the current Nashville studio king Brent Mason, can chicken-pick that guitar to an inch of its life. The constant four-square phrasing can get a bit predictable, but these folks really know how to take two hunks of wood and some scraps of metal and make the most of it.

I rarely have the focus to listen to large works on line – distracted by e-mails, or wanting to get back to composing and playing my own version of “the magic,” but a few months ago I watched a performance of Sophia Gubadulina’s Viola Concerto. It is a work I already knew and really liked (from CD), but the video was very strong. Probably Yuri Bashmet – he plays all those viola concerto things. When I get serious, I dump the computer speakers, plug the audio output into a serious high fidelity audio card and put on decent headphones. A decent high-resolution MP3, combined with good camera work, can be a pretty powerful presentation of music, in the right environment.

I know we all are supposed to hate MP3s (yes, I recorded all my CDs at 24 bit…. I am a “true believer” in bit depth…), but when properly managed, they can get us 90% of the way to “the magic.” And seeing as we can’t really agree on where that final, mysterious 10% comes from, I usually just sit back and enjoy the show.

What a great idea – I think I’ll go see what I can scrounge up on Youtube… gotta run…